Infrared (IR) spectroscopy is a simple and rapid instrumental technique that can give evidence for the presence of various functional groups. If you had a sample of unknown identity, among the first things you would do is obtain an infrared spectrum, along with determining its solubility in common solvents and its melting and/or boiling point.

Infrared spectroscopy, as all forms of spectroscopy, depends on the interaction of molecules or atoms with electromagnetic radiation. Infrared radiation causes atoms and groups of atoms of organic compounds to vibrate with increased amplitude about the covalent bonds that connect them. (Infrared radiation is not of sufficient energy to excite electrons, as is the case when some molecules interact with visible, ultraviolet, or higher energy forms of light.)

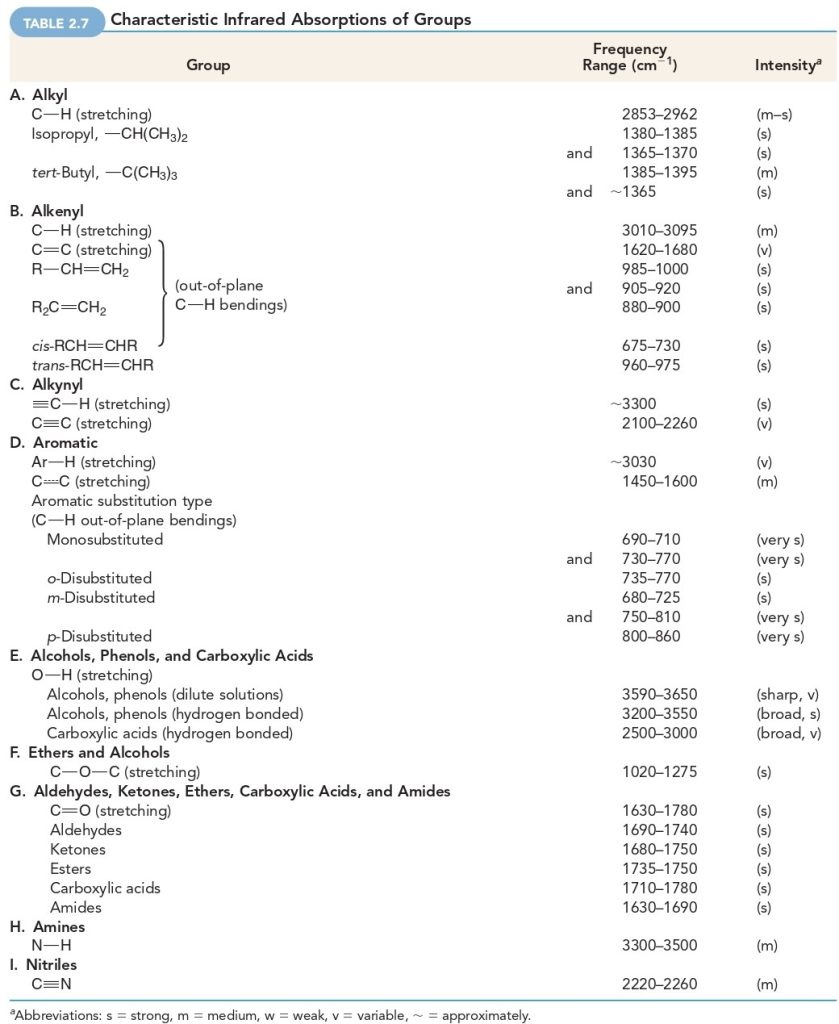

Since the functional groups of organic molecules include specific arrangements of bonded atoms, absorption of IR radiation by an organic molecule will occur at specific frequencies characteristic of the types of bonds and atoms present in the specific functional groups of that molecule. These vibrations are quantized, and as they occur, the compounds absorb IR energy in particular regions of the IR portion of the spectrum.

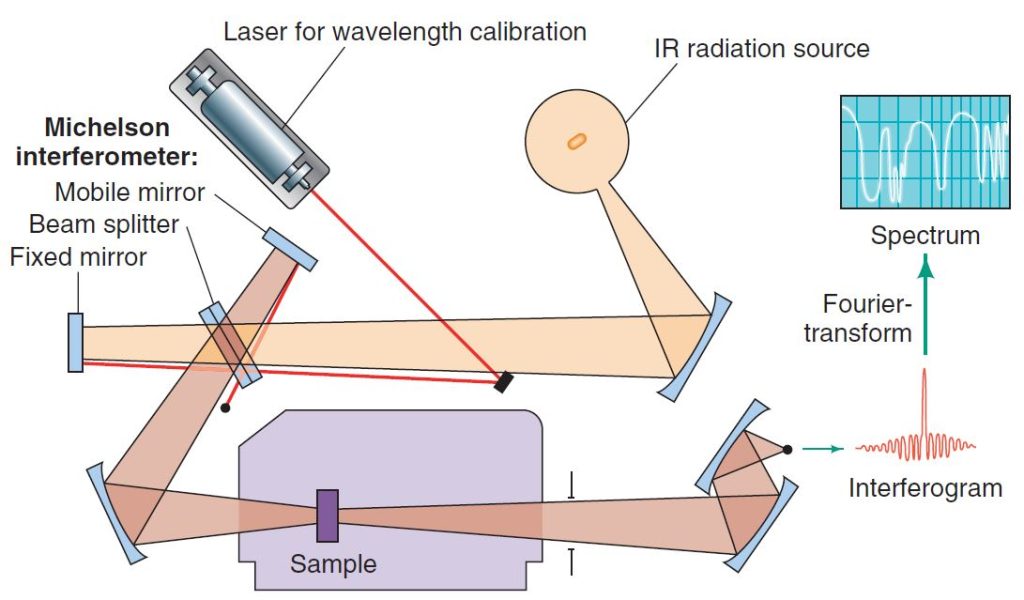

The FTIR method eliminates the need to scan slowly over a range of wavelengths, as was the case with older types of instruments called dispersive IR spectrometers, and therefore FTIR spectra can be acquired very quickly. The FTIR method also allows greater throughput of IR energy. The combination of these factors gives FTIR spectra strong signals as compared to background noise (i.e., a high signal to noise ratio) because radiation throughput is high and rapid scanning allows multiple spectra to be averaged in a short period of time. The result is enhancement of real signals and cancellation of random noise.

An infrared spectrometer operates by passing a beam of IR radiation through a sample and comparing the radiation transmitted through the sample with that transmitted in the absence of the sample. Any frequencies absorbed by the sample will be apparent by the difference. The spectrometer plots the results as a graph showing absorbance versus frequency or wavelength.

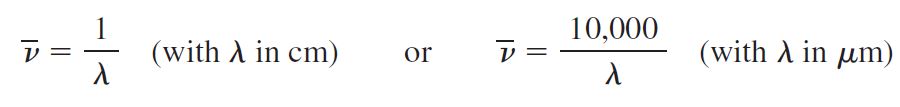

The position of an absorption band (peak) in an IR spectrum is specified in units of wavenumbers (⊽).

Wavenumbers are the reciprocal of wavelength when wavelength is expressed in centimeters (the unit is cm-1), and therefore give the number of wave cycles per centimeter.

The larger the wavenumber, the higher is the frequency of the wave, and correspondingly the higher is the frequency of the bond absorption. IR absorptions are sometimes, though less commonly, reported in terms of wavelength (λ), in which case the units are micrometers (mm; old name micron, m). Wavelength is the distance from crest to crest of a wave.

In their vibrations covalent bonds behave as if they were tiny springs connecting the atoms. When the atoms vibrate, they can do so only at certain frequencies, as if the bonds were “tuned.” Because of this, covalently bonded atoms have only particular vibrational energy levels; that is, the levels are quantized.

The excitation of a molecule from one vibrational energy level to another occurs only when the compound absorbs IR radiation of a particular energy, meaning a particular wavelength or frequency. Note that the energy (E) of absorption is directly proportional to the frequency of radiation (ν) because ∆E = hv, and inversely proportional to the wavelength (λ) because v = c / λ , and therefore ΔE = hc / λ.

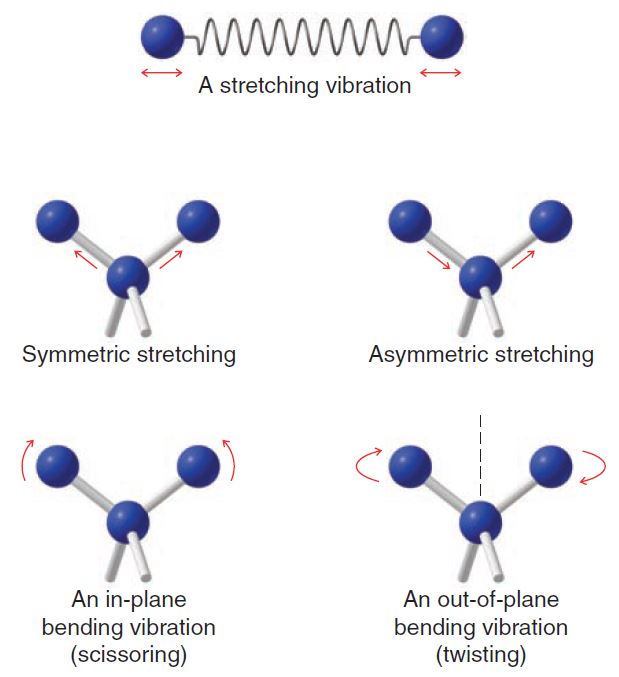

Molecules can vibrate in a variety of ways. Two atoms joined by a covalent bond can undergo a stretching vibration where the atoms move back and forth as if joined by a spring. Three atoms can also undergo a variety of stretching and bending vibrations.

The frequency of a given stretching vibration in an IR spectrum can be related to two factors. These are the masses of the bonded atoms—light atoms vibrate at higher frequencies than heavier ones—and the relative stiffness of the bond. (These factors are accounted for in Hooke’s law, a relationship you may study in introductory physics.)

Triple bonds are stiffer (and vibrate at higher frequencies) than double bonds, and double bonds are stiffer (and vibrate at higher frequencies) than single bonds. Notice that stretching frequencies of groups involving hydrogen (a light atom) such as C−H, N−H, and O−H all occur at relatively high frequencies:

| GROUP | BOND | FREQUENCY RANGE (cm-1) |

| Alkyl | C−H | 2853–2962 |

| Alcohol | O−H | 3590–3650 |

| Amine | N−H | 3300–3500 |

Notice, too, that triple bonds vibrate at higher frequencies than double bonds:

| BOND | FREQUENCY RANGE (cm-1) |

| C𝄘C | 2100–2260 |

| C𝄘N | 2220–2260 |

| C𝄗C | 1620–1680 |

| C𝄗O | 1630–1780 |

Not all molecular vibrations result in the absorption of IR energy. In order for a vibration to occur with the absorption of IR energy, the dipole moment of the molecule must change as the vibration occurs.

Thus, methane does not absorb IR energy for symmetric stretching of the four C-H bonds; asymmetric stretching, on the other hand, does lead to an IR absorption. Symmetrical vibrations of the carbon–carbon double and triple bonds of ethene and ethyne do not result in the absorption of IR radiation, either.

Vibrational absorption may occur outside the region measured by a particular IR spectrometer, and vibrational absorptions may occur so closely together that peaks fall on top of peaks.

Because IR spectra of even relatively simple compounds contain so many peaks, the possibility that two different compounds will have the same IR spectrum is exceedingly small. It is because of this that an IR spectrum has been called the “fingerprint” of a molecule. Thus, with organic compounds, if two pure samples give different IR spectra, one can be certain that they are different compounds. If they give the same IR spectrum, then they are very likely to be the same compound.

Free Download Following Books:

- Fundamentals of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (2nd Ed.) By Brian Smith

- Introduction to Experimental Infrared Spectroscopy Fundamentals and Practical Methods By Mitsuo Tasumi

- Modern Spectroscopy (4th Ed.) By J. Michael Hollas

- Spectroscopic Identification of Organic Compounds (8th Ed.) By Robert M. Silverstein, Francis X. Webster, David J. Kiemle and David L. Bryce